The article is a limited hangout that doesn't mention the South African Institute of International Affairs, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, or the Council on Foreign Relations. The article has a picture of Secretary of State George Shultz shaking hands with Oliver Tambo, the late exiled leader of ANC, at the State Department in 1987. The article mentions that people like Henry Kissinger were invited to International Freedom Foundation seminars to deliver keynote speeches. Among those in attendance was former CIA director William Colby. Shultz, Kissinger and Colby were members of the Council on Foreign Relations. The article talks about Americans who were on the board of Directors of the IFF, and who worked for the IFF in South Africa. Nearly every man mentioned was a United States Intelligence agent at one time or another. Do former United States intelligence agents, continuing working as agents even after they become elected government officials, or are appointed to the US Department of State?

A list of some of the people mentioned in the story with locations and dates of intelligence service follows:

SHULTZ GEORGE P (Council on Foreign Relations Member) Panama 1984, Grenada 1984, Libya 1986

KISSINGER, HENRY A (Council on Foreign Relations member ) South Africa 1969-1977, Philippines 1972, Indonesia 1975, Angola 1976, Britain 1976, Chile 1976,China 1989-1997

COLBY WILLIAM EGAN (Council on Foreign Relations member) Norway 1944-1952, Sweden 1951-1953, Italy 1953-1958, Vietnam 1959-1971, Indonesia 1963-1965, Chile 1970-1973, Japan 1985, Singapore 1985

DORNAN ROBERT K (R-CA) Laos 1981

SELLARS, DUNCAN W (Chairman IFF, 1993) South Africa 1986, Nicaragua 1988

ABRAMOFF JACK South Africa 1983

KEYES ALAN L India 1979-1980, Zimbabwe 1980-1981

BURTON DAN L (R-IN) Mozambique 1986

HELMS JESSE A (R-NC) Argentina 1975-1976, Taiwan 1975, Chile 1976-1986, Panama 1977, Guatemala 1981, Mozambique 1986 ,South Africa 1986

WILLIAMSON CRAIG South Africa 1980-1998

DE KLERK F W South Africa 1986-1996

BOOYSE WIM South Africa 1993

YUILL MARTIN South Africa 1983-1988

CRYSTAL RUSSELL South Africa 1983-1985

LEVENTHAL TODD United States Information Agency

KALUGIN OLEG D USSR 1960-1992

PARKER JAY A South Africa 1984-1985

The description of the International Freedom Foundation printed in the 1993 Encyclopedia of Associations reads,

"*14748* INTERNATIONAL FREEDOM FOUNDATION (Conservative) IFF

200 G. St. NE, Ste, 300 Phone:(202) 546-5788

Washington, DC 20002 Duncan Sellars, Chm.

Founded 1986. Staff:20 Nonmembership. Works to foster individual freedom throughout the world by engaging in activities which promote the development of free and open societies based on the principles of free enterprise, while recognizing and respecting the sovereignty and cultural heritage of nations. Believes that freedom of though and expression, and free association without government interference, is essential to human dignity and without protection from violent coercion, liberty and prosperity are impossible. Works to demonstrate the benefits of a "parliamentary" democracy" and expose the "failures" of a "people's democracy," which the group says, is often referred to as a system of "freedom" but is actually a guise for totalitarianism. Considers totalitarian systems to be the "enemies of freedom" and a threat to the security of the West. Encourages and mobilizes support of indigenous democratic movements. Organizes forums for dialogue and discussion on issues of human rights and free enterprise. Sponsors seminars, fellowships, and international exchanges; maintains speakers' bureau. Telecommunications Services: Fax (202) 546-5488."

"Publications Angola Peace Monitor, monthly Covers developments in the Angolan peace process · Price: $105/year. ISSN; 1045-0513 Circulation 2000. Advertising: not accepted. ·Freedom Bulletin, monthly. Newsletter, includes feature articles on major foreign policy issues. Price: $24/year in U.S. $30/year outside of U.S. ISSN: 0897-5086 Circulation: 221000. i Advertising: accepted. · Freedom Bulletin - UK Edition, 6/year. Newsletter including articles on foreign policy issues from British and European perspectives Price: $10/year; £8 /year in United Kingdom. Circulation 6000. · Freedom Bulletin - Republic of South Africa Edition, monthly, Newsletter including features on developments in South Africa. Price: $20/ year in U.S.; R45/year in South Africa. Circulation: 6000. Advertising: not accepted. · InterAmerican OPPORTUNITIES Briefing, bimonthly. Newsletter; includes business activity and economic reform in Latin America. Price: $105 /year. ISSN: 1055-9299. · Laissezfaire, quarterly Journal on European affairs and European-Third World relations; includes book reviews. Price: $30/year in U.S.; £l0/year in United Kingdom. Circulation: 6000. Advertising; accepted. · OPPORTUNITIES Briefing, bimonthly. Newsletter; includes free market trends and business opportunities in Eastern Europe. Price: $105/year. ISSN: 0960-5088. Advertising: not accepted. · Soviet Perspectives, monthly. Guide to economic reform and business opportunities in the Soviet Union. Price $225/year ISSN: 1055-1042. · Sub-Sahara Monitor, monthly. Newsletter ; includes political and economic issues, periodic country reports, aid and trade briefs, investment analysis, and book reviews. Price: $105/year. ISSN: 1018-1520. · terra nova, quarterly. Journal containing scholarly articles on foreign policy issues, as related to free market economic and political thought; includes book reviews. Price: $24/year. ISSN: 1056-8018. Circulation: 7000. · Also publishes monographs, posters, and reports produces videotapes."

If the International Freedom Foundation is a front for Intelligence organizations do their publications contain information telling intelligence agents what to do?

Why didn't Newsday connect the International Freedom Foundation to the Council on Foreign Relations? Did the Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigate the Council on Foreign Relations/Royal Institute of International Affairs/South African Institute of International Affairs role in creating the racial tension, hatred and genocide in South Africa? If they did, what were their findings? If they did not, don't you think it is about time they did? The Newsday article follows:

NEWSDAY Sunday July 16, 1995 Front for Apartheid Washington-based think tank said to be part of ruse to prolong power This article was reported by Dele Olojede in South Africa and Timothy M. Phelps in Washington, and was written by Olojede.

|

The International Freedom Foundation, founded in 1986 seemingly as a conservative think tank, was in fact part of an elaborate intelligence gathering operation, and was designed to be against apartheid's an instrument for "political warfare" against apartheid's foes, according to former senior South African spy Craig Williamson. The South Africans spent up to $1.5 million a year through 1992 to underwrite "Operation Babushka," as the IFF project was known.

The current South African National Defence Force officially confirmed that the IFF was its dummy operation.

"The International Freedom Foundation was a former SA Defence Force project," Army Col. John Rolt, a military spokesman, said in a terse response to an inquiry. A member of the IFF"s international board of directors also conceded Friday that at least half of the foundation's funds came from projects undertaken on behalf of South Africa's military intelligence, although he refused to say what these projects were except that many of them were directed against Nelson Mandela's African National Congress.

A three-month Newsday investigation determined that one of the project's broad objectives was to try to reverse the apartheid regime's pariah status in Western political circles. More specifically, the IFF sought to portray the ANC as a tool of Soviet communism, thus undercutting the movement's growing international acceptance as the government-in-waiting of a future multiracial South Africa.

"We decided that, the only level we were going to be accepted was when it came to the Soviets and their surrogates, so our strategy was to paint the ANC as communist surrogates," said Williamson, formerly a senior operative in South Africa's military intelligence, who helped direct Babushka. "The more we could present ourselves as anti-communists, the more people looked at us with respect. People you could hardly believe cooperated with us politically when it came to the Soviets."

The South Africans found willing, though possibly unwitting, allies in influential Republican politicians, conservative intellectuals and activists. Sen. Jesse Helms, now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, served as chairman of the editorial advisory board for the foundation's publications. Through a spokesman, Helms said that he did not know anything about the foundation.

"Helms has never heard of the International Freedom Foundation, was not chairman of their advisory board and never authorized his name to be used by IFF in any way shape or form. We never had any relationship with them," Mere Thiessen, a Helms spokesman, said.

Rep. Dan Burton, who was the ranking Republican on the House subcommittee on Africa, and Rep. Robert Dornan were active in IFF projects, frequently serving on its delegations to international forums. Alan Keyes, currently a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, also served as adviser. (He did not return a call seeking comment.) The Washington lobbyist and former movie producer Jack Abramoff, and rising conservative stars like Duncan Sellers, helped run the foundation.

All those contacted denied knowing that it was controlled and funded by the South African regime.

Although there are strong indications that U.S. laws may have been broken some IFF officials have admitted in interviews that they knew that South African military intelligence money helped pay for the foundation's activities in Washington there is no clear evidence that the politicians associated with IFF either took campaign contributions or otherwise directly benefited financially from the foundation .

Under U.S. law, anyone who represents a foreign government or acts under its orders, direction or control, has to register with the Justice Department as a foreign agent. Asked if a "think-tank" sup up and supported by a foreign government has to register, a Justice official said, "If the foreign [government] has some say in what they are doing and, obviously, if they are funding it they probably do then they probably do have to register." Violation of the law carries a fine up to $10,000 and a prison term of up to five years.

Several key figures involved in the IFF and contacted by Newsday denied any knowledge that the foundation was a front for the political agenda of a foreign government. Duncan Sellers, now a Virginia businessman, said, "This is nothing I ever knew about. It's something that I would have resigned over or closed the foundation over. I would have put a stop to it."

"The Congressman didn't know anything about it," said a spokesman for Dornan, Paul Morrell. "This is all news to him if it is true." Morrell described Dornan's impression of the IFF as simply "pro-freedom, pro-democracy, pro-Reagan."

Phillip Crane, another U.S. representative listed as an IFF editorial adviser, joined the board in 1987 at the request of Abramoff, said an aide, and by 1990 had quit. "He never attended a board meeting that he can recall," said the aide, Bob Foster. "He had no idea that any such situation [intelligence connections] existed."

Williamson said that the operation was deliberately constructed so that many of the people would not know they were involved with a foreign government. "That was the beauty of the whole things guys pushing what they believed," he said. Helms for example, voted against virtually every punitive measure ever contemplated against South Africa's white minority government, however mild. And Burton was nearly hysterical in arguing against sanctions that a large bipartisan majority passed in 1986 over President Ronald Reagan's veto, at one point warning that "there will be blood running in the streets" as a result.

But in some cases, such as Abramoffs, the relationship with the South African security apparatus was more than merely coincidental, according to Williamson and others. A former chief of intelligence, now retired, said emphatically that the South African military helped finance Abramoffs 1988 movie "Red Scorpion." The movie was a sympathetic portrayal of an anti-communist African guerrilla commander loosely based on Jones Savimbi, the Angolan rebel leader allied to both Washington and Pretoria. Williamson also said the production of "Red Scorpion" was "funded by our guys," who in addition provided military trucks and equipment -as well as extras .

Abramoff reacted with anger when told of the allegations Friday, saying his movie was funded by private investors and had nothing to do with the South African government. "This is outrageous," he said.

Details of South Africa's intelligence operations in the last years of apartheid have begun to rapidly emerge with the imminent establishment of a Truth Commission by the Mandela government. The commission will elicit confessions of "dirty tricks" by apartheid's foot soldiers and their Commanders, in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Williamson, for instance, recently revealed that he was involved in the assassination of Ruth First, wife of the ANC and South African Communist Party leader Joe Slovo, and other anti-apartheid activists.

In South African government thinking, the IFF represented a far more subtle approach to defeating the anti-apartheid movement. Officials said the p!an was to get away from the traditional allies of Pretoria, the fringe right in the United States and Europe, "some of whom were to the right of Ghengis Khan," said one senior intelligence official. Instead, they settled for a front staffed with mainstream conservatives who did not necessarily know who was pulling the strings.

"They ran their own organization, but we steered them, that was the point," Williamson said.

"They were very good, those guys, eh?" said Vic McPheerson, a police colonel who ran security branch operations and participated in the 1982 bombing of the ANC office in London. "They were not just good in intelligence, but in political warfare."

Starting in 1986, when Reagan failed to override comprehensive U.S. economic sanctions, the South African government began casting about for ways to survive in an international environment more hostile to apartheid than ever. A very senior official in South African military intelligence, to whom IFF handlers reported at the time, said the operation cost his unit between $l million and $1.5 million a year. The retired general said the funds represented almost all of the IFF's annual operating budget, although the foundation gained such legitimacy that it began to attract funding from individuals and groups in the United States.

On at least one occasion, the IFF had trouble accounting for its money. It was unable to comply in 1989 with a New York State requirement that it provide an accountant's opinion confirming that its financial statements "present fairly the financial position of the organization." It was eventually barred, in January, 1991, from soliciting funds from New York. According to financial records provided by Jeff Pandin, the foundation's last executive director in Washington, IFF revenue in 1992 dropped by half of the preceding year's, to $1.6 million. It just so happened that President Frederik W. de Klerk ended secret South African funding for the foundation in 1992, in response to pressure from Mandela to demonstrate that he was not complicit in "Third Force" activities. Pandin expressed shock that much of the organization's money had been coming from clandestine South African sources. "I worked for the IFF from Day One to Day End," he said. "This is complete news to me." He said he once had met Williamson when he was in Mozambique, but was unaware of any official links.

On the surface, the IFF's headquarters was in north-east Washington, D.C., , at 200 G Street, next door to the Free Congress Foundation, another conservative institution. From that base, it launched campaigns against communist sympathizers and perceived enemies of the free market. It broadly supported Reaganism, and its principal officers ran with the Ollie North crowd. But it always paid special attention to ANC. When Mandela made his first visit to the United States in 1990, following his release from prison, the IFF placed advertisements in local papers designed to dampen public enthusiasm for Mandela. One ad in the Miami Herald portrayed Mandela as an ally and defender of Cuba's Fidel Castro. The city's large Cuban community was so agitated that a ceremony to present Mandela with keys to the city was scrapped.

The IFF published several journals and bulletins, in Washington and in its offices in Europe and Johannesburg. One of its contributors was Jay Parker, an African-American who was a paid public relations agent of successive apartheid regimes throughout the 1970s and 1980s. People like Henry Kissinger were invited to IFF seminars to deliver keynote speeches. The foundation brought together the together the world's top intelligence experts at a 1991 conference in Potsdam, Germany, to mull over the changing uses of intelligence in the post-Cold War world. Among those in attendance was former CIA director William Colby and a retired senior KGB general, Oleg Kalugin. The IFF also waged a major but not surprisingly futile campaign for U.S. retention of the Panama Canal. But its main purpose was always to serve the ultimate goals of the South African government, according to those who helped nudge it in that direction. The former senior South African military intelligence official said he traveled to the United States and Canada in 1988 as a guest of the IFF. But the real reason for his trip, he said, was to try to strengthen South African intelligence operations on the ground, at diplomatic posts and the North American offices of Satour, the country's tourism promotion agency.

"I was surprised at the kind of access the IFF operation provided us," said Wim Booyse, who went by the title of Senior Research fellow at the Johannesburg office of the IFF. Booyse said when he visited Washington In 1987 to attend IFF-sponsored seminars, part of the propaganda training he and other visitors received came from a disinformation specialist at the United States Information Service, an official he identified as Todd Leventhal. Leventhal said in response that he remembered meeting with Booyse and possibyly a few other IFF people, but gave no formal talk and talked to them only about countering disinformation, not spreading it

Far from being a mere branch of the IFF, the Johannesburg office was in fact the nerve center of IFF operations worldwide. According to Martin Yuill, who served as administrator of the "branch," he began to realize that perhaps Johannesburg was not just a branch office after all, since it was always deciding how much money the other offices, Including the Washington headquarters, should have. "I guess one would have to conclude that that was the case," he said.

Although he insisted that the IFF was no clandestine operation, Russell Crystal who ran the Johannesburg office, said it was vital to the foundation. He said Friday in an interview that "jobs" for South African intelligence provided at least half of total IFF revenue, and that he sometimes asked military intelligence to send the fees from these "jobs" directly to the Washington office of the IFF.

"The military intelligence, there were certain things they wanted done -- tackling the ANC as a terrorist-communist organization," Crystal said. "The projects we did for them, they paid for. " He added that it was not impossible that South Africa accounted for far more than his estimated 50 percent, of IFF revenues.

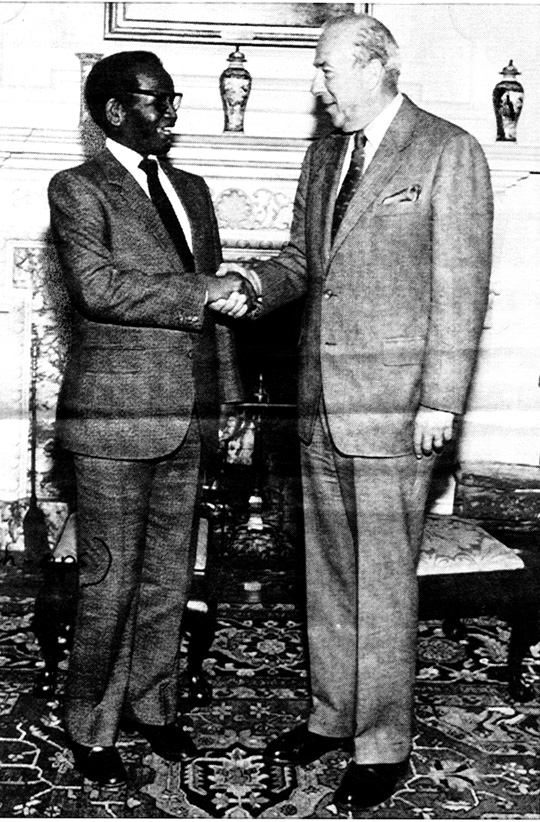

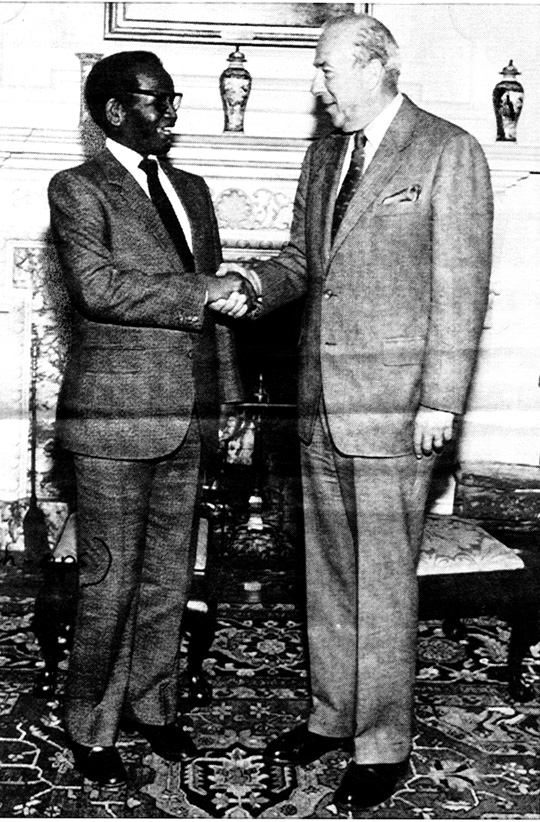

As an example of this "tackling," Crystal cited the targeting of Oliver Tambo, whenever the late exiled leader of the ANC traveled around the world. Once, when Tambo visited with George Shultz, then-secretary of state, the IFF arranged for demonstrators to drape tires around their necks to protest the "necklace" killings of suspect ed government informers in black townships in South Africa.

"The advantage of the IFF was that it pilloried the ANC," said Williamson. "The sort of general western view of the ANC up until 1990 was a box of matches [violence] and Soviet-supporting -- slavishly was the word we latched on. That was backed up with writings, intellectual inputs. It was a matter of undercutting ANC credibility."

By 1993, the IFF effectively shut down after de Klerk pulled the plug on many politically motivated clandestine operations. But the IFF did not go down before one final parting shot.

In January that year, the foundation financed a investigation into alleged human rights abuses during the 1980's at ANC guerrilla camps in Angola. Bob Douglas, a South African lawyer, concluded there was evidence of torture and other abuses, forcing the ANC to acknowledge some abuses. Douglas said Friday he did not believe that the IFF worked for military intelligence. "I did a professional job for which I charged professional fees," he said crossly. "I did my job of work, I finished my work, and had nothing to do with it since then."